Have you ever asked yourself what might have happened in your life if you had made different choices? I have.

The apex of my career in Europe happened at one of the most difficult times of my life. I won the Copa del Rey with a last-second basket and was Season MVP and Finals MVP. But I was down. My sister had died just the week before.

The only moment I wasn't thinking about Michelle was when I was on the court, only there could I distract myself from the grief. I blamed myself. Should I have left Brazil? Did I really have to?

The only thing I was sure about was that I had done all I could at the time. I even hid medicine in my suitcase to take back to Brazil.

My parents went over to watch, as a surprise. It was a very emotional moment. The whole team jumped on top of me after the game, all of us celebrating and crying at the same time.

Michelle was also a basketball player and had come with my brother to spend one Christmas in Spain. Everything seemed fine. I remember that two or three months later, my dad called. She had leukaemia. Up until that call I didn't even really know what it was. What I know is that my dad was crying on one end of the call and I was crying on the other. We thought: 'It's going to be OK. She's strong, she's going to beat this.'

In reality, we went through highs and lows. After a year, the cancer had disappeared. She started playing again, and it was a moment of great joy. But there was still that little bit of caution, because we knew it could come back. And it did.

We thought about bringing her to the United States. I'd been drafted by the Spurs, and they offered a plane to bring her to the US. Only she was already so weak that we didn't think she could handle the long journey on a plane. So, she stayed at a hospital in Campinas [in São Paulo]. My mom had to move there from Blumenau, in Santa Catarina. She pretty much slept in a hospital chair for two years.

The problem is that, when leukaemia comes back, you've only got one chance: a transplant. We had a 50% chance, but neither my bone marrow nor my brother's were a match. We started a project to try to find a donor. We got the whole city out, spread the word from Blumenau to Rio de Janeiro, where we found someone who was compatible.

Then another problem came up: to do the transplant, we needed some medication that was out of stock in Brazil.

How are we going to find the medication? She had to have the operation ASAP. I couldn't wait. Neither could she. So, I bought the medication in Spain and secretly took it to Brazil.

The doctors told me that this was a common situation and that, if I brought the drug, they would do the transplant. They told me that I wasn't the first person to do this. I bought a suitcase, put a cooler inside of it, filled it with ice and boarded the plane to Brazil.

It was the only way to save my sister's life. What would you have done in that situation?

Unfortunately, her body rejected the bone marrow. I had already gone back to Spain when I got one of the most difficult phone calls of my life: "Tiago, come to Brazil because I don't know how much longer she's got."

When I got there, she was tethered to machines. All swollen. I remember saying to the doctors; "I don't want her to be in pain, please. Do something so that she's not in pain." And that was it. Two days after I arrived, we took her to Blumenau, our city, for the funeral.

And then basketball became my escape mechanism once again.

After going through such an experience, you might say that everything that happened afterwards was easy. But it wasn't. Sport knocks you down and lifts you up, knocks you down and lifts you up; and it's cruel because it's just like that: relentless.

A year after that final, I made the move from Europe to the NBA. I was the best player in my position in European basketball when I went to the San Antonio Spurs, in 2010. I finally had made it to the NBA! But I didn't play.

Imagine the situation: the best player on one continent arrives on another and simply doesn't play. Was I doing something wrong? Did I deserve to be there?

I had thick skin, but at that moment I asked myself: "Is the NBA too big for me?"

Even the Spurs coach noticed. One day, after a game, I was going back to the bus, and Gregg Popovich grabbed me by the arm.

- Sit here. Are you sad? Are you mad?

- Yeah, I'm sad and I'm mad.

- Is it because you're not playing?

- Yeah.

- Well, then you'd better not stay sad because you are not going to play. The team's ready. The team is set. It's the same guys as last year. Keep training hard. You're training well. Keep working and next year you'll play more.

That relieved the tension. I wasn't doing anything wrong, nobody had anything against me, I wasn't training less than I should be. At least I knew I was doing the right thing.

That honesty was so important. It's rare for a coach to be that honest and clear with a player. He never promised that I'd play. He said I wasn't going to play and that was it. Do you know what happened the next year? I played.

In those first games, everything happens very quickly on the court. It's out of this world. The players are much bigger, the arms much longer. The timing of a pass, or of a shot. Everything changes. It's really tiring, too, because you're up and down, up and down, the speed of the game is faster. I had to adapt physically. I put on 22lbs of muscle in the NBA.

My first NBA game was at the Staples Center, against the Los Angeles Clippers. I still remember my first play. It was a pick and roll with Manu Ginóbili, who passed the ball for me to dunk. It was a moment that defined that joy of being in the NBA, being part of the dream, the greatest league in the world.

That dream had been laid out in front of me when I was 14. Do you know what it's like to be 14 and see the NBA as an actual possibility?

For you to understand the circumstances, we've got to go back to where it all began. At 12, 13, I had that growth spurt. At 14, I was already 6'7", and trained with the adult team in Blumenau. Learning to battle against the older guys made playing against guys my own age really easy. You couldn't even compare it.

During the South American Championships with the U16 Brazil team in Chile, I got invitations from a few scouts who saw me play. And a team from Spain, Baskonia, asked me to go over and check out the club, the city of Vitoria-Gasteiz, the country.

I went there with my dad and my mom, trained with the guys. Everything was so different. I'd come from a little town in Santa Catarina [in the South of Brazil] and was in Europe, in a new country, speaking another language.

But my parents didn't want that change. Everybody could see my potential, but they wanted to take a look at the alternatives. Vasco [da Gama, a team in Rio de Janeiro,] was putting together a great team and had already voiced their interest in me - it was around the same time that Nenê went there and, shortly after, was drafted to the NBA - and there was also the possibility of playing without pay in the USA, at the high school level, and living with Danny Ainge, who is now the Boston Celtics' general manager.

When I found out that in Spain it was a ten-year contract with a buyout clause for the NBA, it weighed heavily on my decision. I was 14 and they were already talking about NBA! Apart from that, I was going to get paid from day one, and the contract included yearly trips for my family to come visit. I went.

Up until then, everything was easy. Even saying goodbye. Whenever I had to travel it was just, "Buh-bye", then I'd turn around and go my way. I suffer more if I stay there hugging and talking for three hours.

Things got harder when I started training over there. The sessions were tougher than I was used to. My mom lived in Spain with me for the first three months to help me adapt. I remember getting back from practice and asking for a massage because I was in so much pain. One day, we had to sneak out because I wanted some pain relief rub. I didn't want to tell anyone that I was tired, that everything hurt.

I wasn't going to complain, I didn't want to show them any weaknesses. I wanted them to be happy to have me on the team. I never complained.

Not even in the hardest practices of my life. In my second year in Spain, we had a Serbian coach who would make us get up at 6 a.m. to go run up a mountain before breakfast. The whole team would get back, eat and go run shuttles on a soccer field. We'd go to the gym, come back, have lunch, rest a little in the afternoon and then practice basketball.

I witnessed people vomit blood, fall on the floor with every muscle in their body cramping. It was crazy. One day, I cried. Hidden away, of course. I told myself that I'd go back to Brazil. If I had to go through that to become a player, then I wasn't going to become one.

But I didn't give up, the other players didn't give up. At the end of that period of training, we realized it wasn't physical. It was mental. That's what they were trying to teach us.

I still talk to all the guys who were on that team. We learned that at the end of a game, when we're too tired, with that monumental pressure bearing down on us, nothing compares with what we went through in those practices.

Ultimately, that madness made me thick-skinned, both in my career and in my personal life. That was how I survived losing Michelle and what happened to me in my last years in basketball.

After being the first Brazilian NBA champion, I was the first in the league to play with a prosthetic hip. It was more than 12 months of recovery, a lot of physiotherapy, to be able to come back and play. And it's not like I came back playing spectacularly well. Not at all. I was pretty mediocre. But I was so happy to be back that I didn't care.

Things started to go wrong towards the end of my spell with the San Antonio Spurs. I had problems with my calves. There were two or three tears. When I went to Atlanta, the physiotherapist told me in my first session: "Tiago, your hip isn't moving too well, it's pretty stiff." I said, "Well, it's always been like that. Ever since I can remember, I've never had much movement." "Should we do a scan and see how it looks?"

We did the scan, and the doctor came to talk to me. Not one. Two or three doctors. Straight away, I thought it was strange, a conference of physicians. "We have some news for you: you don't have any cartilage left. This pain that you're felling will only get worse and you'll probably have to stop playing. You're pretty much running bone on bone."

At first, the pain wasn't too bad. But that little bit of pain limited the movement of my leg and overloaded my calf. It limited the movement of running, so I didn't fully stretch out my leg forwards or backwards. To relieve the pressure on my calf, the advice was to lengthen my stride. But when I did that, the pain in my hip got worse and worse and worse.

As it was something that had been happening for years, it's hard to know why it happened. It might be a genetic issue. It might be due to all those runs up the mountain. It might be because I went pro too soon, or practiced in one way, making the same movement over and over. I just know that I didn't care about the reason. The only thing in my head was how to relieve the pain.

It got to a point that it was so unbearable I couldn't even put a sock on my foot. I had to take two or three pills just to practice. I had injections to play. My liver wasn't even processing the drugs anymore.

As an athlete, you take a lot of pain medication. It's not good, but you end up doing it. Fans expect the best from you, and you want to play without pain so you can give it to them.

But nobody knows what's going on inside your body. Nobody knows that Tiago is in pain. The only thing that comes out in the newspaper the next day is "Tiago played badly".

So, you take the medication, you take the injections. You want to reach your best level of performance within the rules. I spoke to the best hip specialists in the US. I even spoke to the specialist who operated on [tennis player] Guga Kuerten. The only solution they could come up with was a prosthetic hip.

"Tiago, I've got a new prosthesis. There was a hockey player who played with this prosthesis. There was an indoor football player who had hip replacement and played. If you do the surgery, you'll be the first NBA player to have it. I don't see any other way for you to keep playing."

That was right before the Rio Olympics. Or to put it bluntly: if I have the surgery, I won't play the Olympics. Either way, I wouldn't be able to compete. But if I have the surgery there is absolutely no chance of that happening. It was a moment of wisdom, of God to tell me what I had to do.

My life was being affected by the injury. I wasn't sleeping well because of the pain in my hip, I couldn't dress myself properly, I took so many things just to play. I didn't want that. How could I carry on with my hip like that? I'm going to have the operation.

The fact I had a chance to play again was important. There was also an element of pride. To show that I could do it. I was going to be the first guy to play in the NBA with the prosthesis.

It's not an easy operation.

They cut your glute muscle down the middle, dislocate and sand down the head of the femur. Then, they put a metal helmet over it. After that, they put another piece inside the hip that acts as a socket for the metal helmet. It's called hip resurfacing. It's a modern kind of prosthesis made for people to continue to be able to be physically active. It's not like the kind of hip replacement an elderly person might have. For those ones, they cut the head of the femur off, put a metal pin down the middle of the bone and the whole femoral head is new. Not with mine. There's no pin down the middle of the bone. They just put the helmet around the femur.

My brother, Marcelo, was with me at the hospital. He had to help me with everything. To go to the bathroom, sit on the toilet, take a shower. Everything. I could only support myself on one leg and that was it.

At that time, everything was a challenge. I tried to make it like a sport. Every little step was a victory. The day that I stopped using the first crutch. The day that I stopped using both crutches. The day that I managed to walk alone. The day that I managed to jog for the first time. The day that I shot a basketball for the first time. They were small victories that I celebrated a lot.

There were people who questioned me, obviously. "What are you doing? You've already had your career." But I wasn't going to throw in the towel while I still had a 0.5% chance of getting back on a basketball court. I just wasn't.

Those were 13 hard months of training alone, spending five, six hours a day strengthening my leg, swimming, biking, running on a treadmill. In the middle of all that, I tore my hamstring trying to play again. It's hard, because you end up changing the way you run. There are muscle groups that you didn't use before and suddenly you're using too much. They end up tearing.

You relearn to run. Walking first, then a little jog, then running, then changing direction, then jumping. There were a lot of obstacles before I could get back on a real court.

After the surgery, I got traded to Philadelphia. I went there saying: "Have faith in me because I'm going to train, I'm going to do everything I can to come back and play." It was a daily and constant struggle. They even sent me to the G-League, a sort of development league for the NBA, to get some practice minutes.

It's not very common for a player who has won an NBA Championship to go down and play the G-League. I wanted to show them that I wanted this. Really wanted it. I even played a game in the G-League to show them that I truly meant it.

I wanted to play one basketball game in the NBA even with an iron hip. That was my goal. And like I said, it was my mental strength that helped me through it.

I played eight games at the end of the season. I took a two-week vacation and went back to practice. I started to feel pain on my left side. The next day, more pain, and more pain. That same pain that I felt on my right side all those years, I was now feeling on the left.

I called the same doctor. We tried another treatment with injections inside the hip. I went back to practice and? Pain, pain, pain. I called the doctor, and he said: "Tiago, unfortunately this hip is just like the other. Bone on bone. Now it's your decision. Do you want to have the same surgery on the other side, or do you want to stop playing?"

Analyzing the situation I was in, and my age? If I had to have the surgery again, it would be at least a year to maybe come back and play. Going through all that again. With the first operation, I'd lost about 40% of my speed. With another, it'd be impossible to play professional basketball again.

With one prosthetic hip, you might be able to get away with it, but two? In a league like the NBA, which gets faster and faster all the time, with fewer and fewer players in my position. The time had come. I spoke with my wife, and decided to stop playing.

Maybe I could have carried on in Europe, but there came a time when I had to think about my life outside of sports. My first hip replacement will last 20 years. So, in 18 years, I'm going to have to operate on it again.

I'll probably have to have another on my left hip, too. I'm talking about four operations. I'd have to live at the hospital. I don't want my life to be like that.

A time comes that you have to think about your future walking down the street. I don't want to be in a wheelchair. If the surgery goes wrong, if you get an infection in the bone or something like that, you're screwed? I can try my luck once. But I won't risk it too many more times.

Now, it's time for me to discover what I'm good at away from the court. I know what a team needs to win a championship. I know how a team has to train. I know how the process of selecting players works. I still don't know what I want to do before the end of my career. But I'm lucky enough to be with the Brooklyn Nets, a team that's giving me the opportunity to learn and to start a new path.

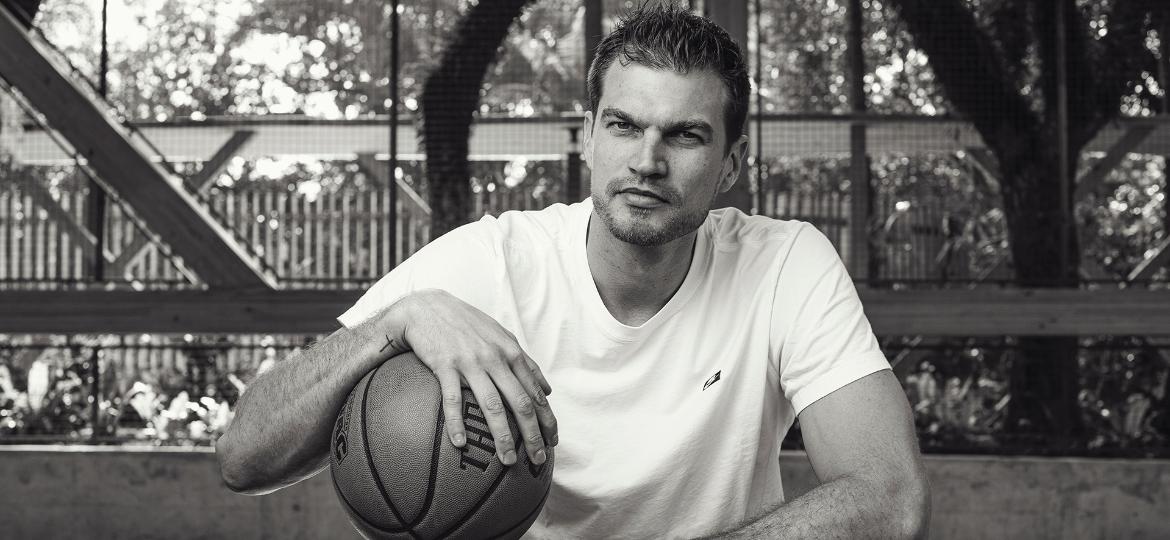

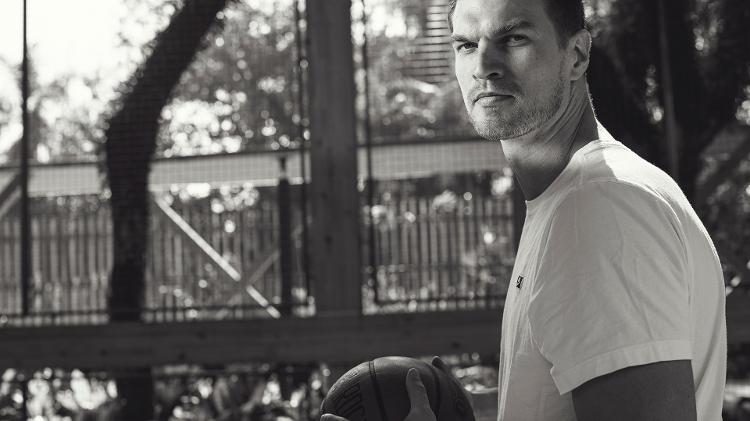

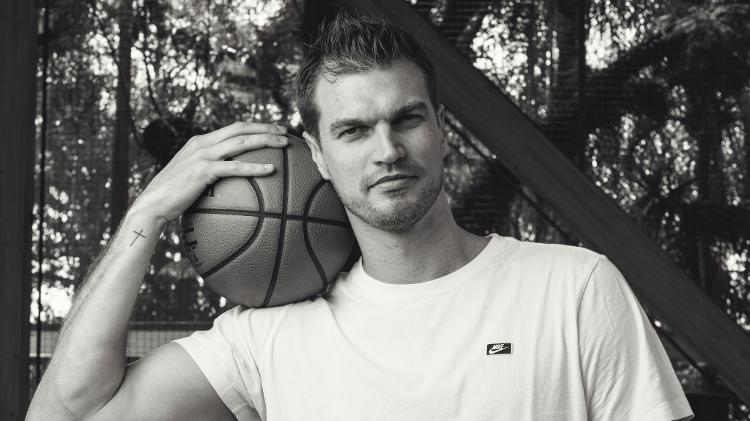

Tiago Splitter is a former basketball player. He won the 2014 NBA Championship with the San Antonio Spurs, and will be Brooklyn Nets' player development coach this upcoming season.

Originally published in Portuguese, edited by Bruno Doro, Fernanda Schimidt and Giancarlo Giampietro.

English version by Joshua Law, edited by Fernanda Schimidt

ID: {{comments.info.id}}

URL: {{comments.info.url}}

Ocorreu um erro ao carregar os comentários.

Por favor, tente novamente mais tarde.

{{comments.total}} Comentário

{{comments.total}} Comentários

Seja o primeiro a comentar

Essa discussão está encerrada

Não é possivel enviar novos comentários.

Essa área é exclusiva para você, assinante, ler e comentar.

Só assinantes do UOL podem comentar

Ainda não é assinante? Assine já.

Se você já é assinante do UOL, faça seu login.

O autor da mensagem, e não o UOL, é o responsável pelo comentário. Reserve um tempo para ler as Regras de Uso para comentários.